Ed Kerns has been exploring levels of consciousness for years and using layers of paint to create an abstract understanding of awareness. His Octopus Meditations exhibition, which opens at 6 p.m. on April 7 at Brick and Mortar Gallery in Easton, Pa., is another manifestation of his perception of consciousness.

Paintings from the series have been selected by Lafayette College’s biology department for permanent display in the $75 million Rockwell Integrated Sciences Center (RISC). Kerns’ work will be an appropriate complement to the RISC, which will be home to programs in biology, computer science, and environmental science and studies, house the IDEAL Center for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, the Daniel and Heidi Hanson ’91 Center for Inclusive STEM Education, as well as provide additional space for neuroscience.

Kerns, Clapp Professor of Art at Lafayette College, was inspired by computer engineer Bernardo Kastrup’s article in Scientific American about levels of consciousness, Sy Montgomery’s book The Soul of an Octopus, and numerous collaborations with neuroscientists and biologists over his 45-year career.

“It’s something I have been thinking about for years in visual collaborative work with neuroscientists, computer scientists, and biologists,” Kerns says. “In the article Kastrup said ‘mechanisms of metacognition are entirely unrelated to the problem of how the qualities of experience could arise from physical arrangement.’”

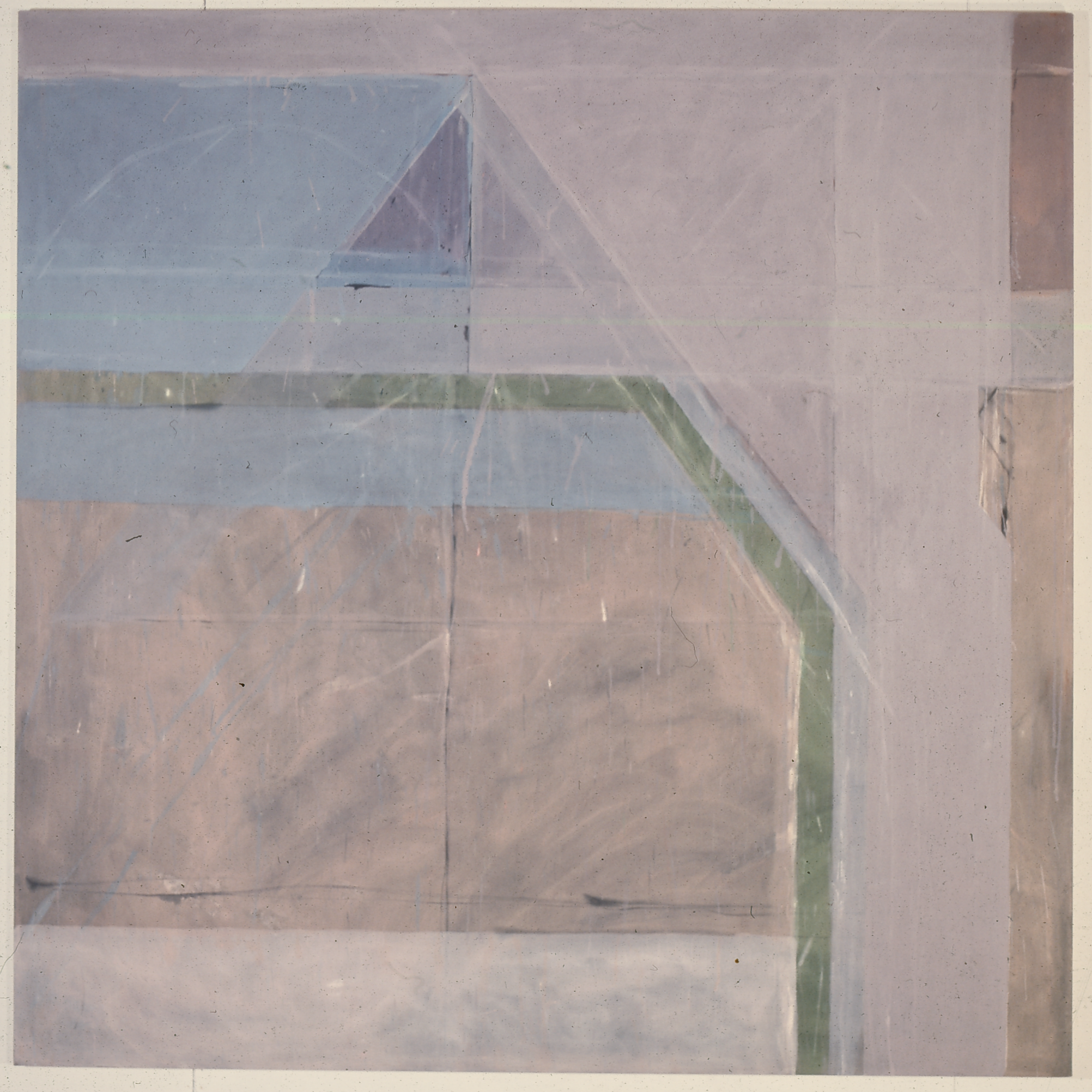

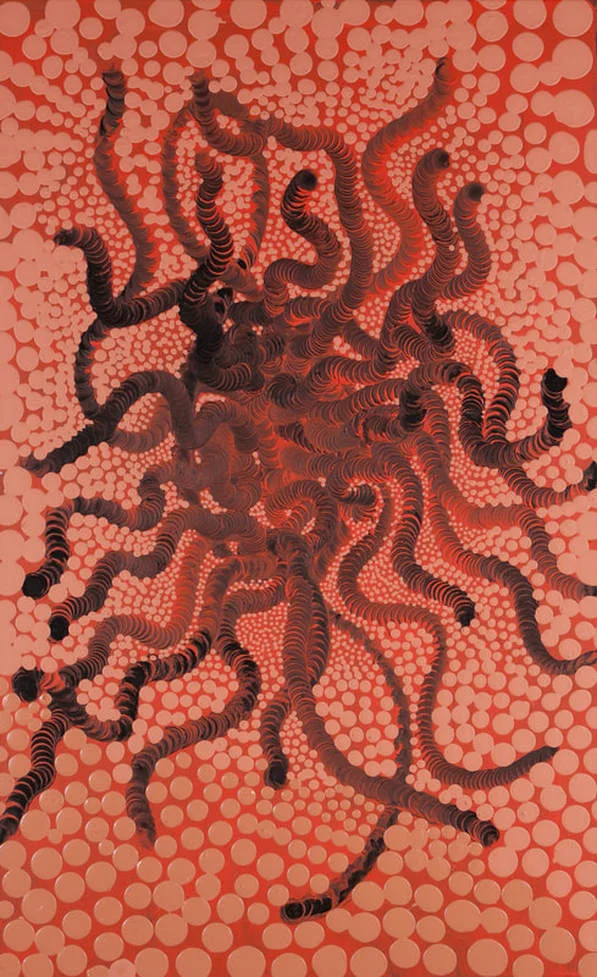

“I think and model subjective experience with paint, and a layered approach is what I use,” Kerns says. “Enter the mimic octopus - a creature that can change shape and color at will. What a treat to contemplate how that might work or look.”

The series "Octopus Meditations" is another manifestation of consciousness, he says.

“I wondered what octopus consciousness might look like,” Kerns says. “It’s sort of a silly question, but it’s really about a synthetic idea that a person in a meditative state might reflect on.

“They are brilliant. They have nine brains and an integrated network, which presupposes a different kind of awareness or consciousness. Humans have a central processing unit with the brain and neurons intimately connected with our body.”

Kerns says everyone knows that cortisol and stress cause things to happen or that we can shut down very easily if too much stimulation goes to the central processing unit.

“An octopus can handle things locally,” he says. “There is a little brain at the top of each of the tentacles. As invertebrates, they have all this surface area from which they can receive telemetry and not shut down.”

“Their perception of the world, however, is likely to be very different from ours given the distinctive organization of their nervous system,” says Elaine Reynolds, associate professor of biology. Kerns “perceives a rich tactile topography of movement and superposition, along with familiar visual patterns of symmetry, bubbles, and cells, representing the physical basis of all matter.” Kerns’ art envisions it through an imaginary world.

“So I’ve been working on what consciousness means,” he says. “Not what goes on when we think, but what it really means. I read a story once about Jonas Salk, who invented the polio vaccine. He was riding in the back of a taxi cab and got an idea of how to defeat the virus by imagining he himself was the virus and could figure out a way to kill himself. If you were a scientist today applying for a grant from other scientists, you probably wouldn’t get it if you talked like that.”“So the octopus lives in this fluid environment with this loose skin, and they have all these perceptual characteristics,” he adds. “So I wonder and think about that idea and make visual systems seeing what emerges and build complex imagery. I’ve been working on this idea for 15-18 years, painting new worlds.”

“I love calamari, but I don’t eat it anymore because I have come to know octopuses,” Kerns says.

-Brian Hay, Lafayette College Communications Division. April 2018